Inside Kyoto Station Complex

I imagined Kyoto, from what I had read that it was the ancient capital of Japan and a repository of great traditional temples and gardens, to be a place where you wandered through winding lanes like an old Japanese painting. How wrong I was! It is a large ultra-modern city with vast hordes of people straining even the most up-to-date infrastructure. To me it seemed even faster and more futuristic than Tokyo. The vast station complex with its huge open air atrium and an 11 storey outdoor escalator seemed to be lifting us to the moon (we had a full moon on our last night as we flowed endlessly up to the sky). Everywhere we went, even at the famous traditional sites in the woods and gardens on the outskirts, were so crowded with people that walking was often reduced to a frustrating shuffle.

In Australia we might decry the obsession with the selfie, but it’s nothing like the tourist sites in Kyoto with all the young, many dressed in Geisha-like gear, sporting phones on selfie sticks, posing and clicking en masse. 95% of the tourists seem Japanese, the trendy youth, the families and the old and the common feature is that everyone seems happy and relaxed, completely oblivious to the crowds.

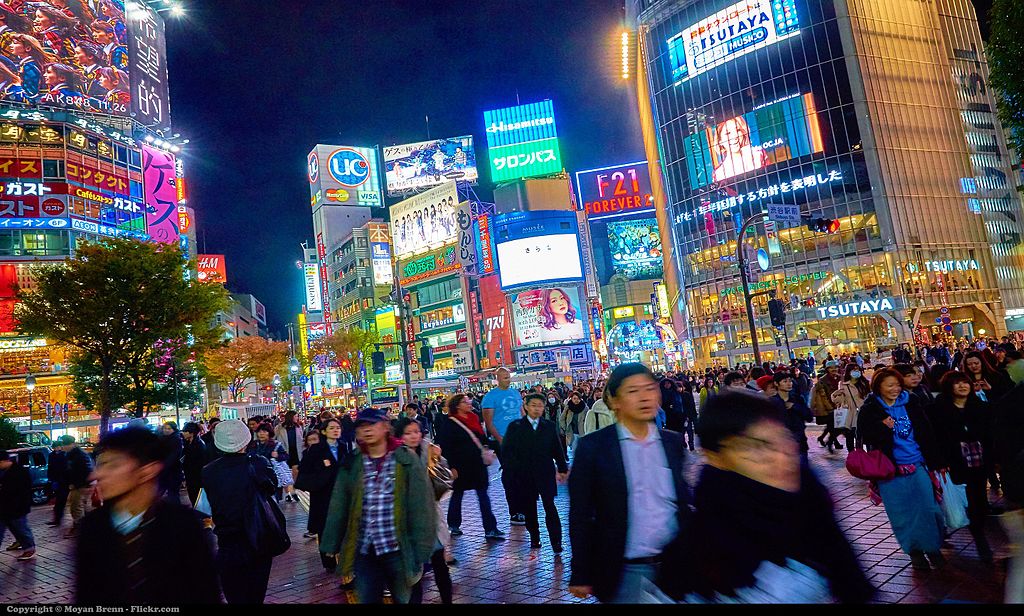

We worked out the public transport system pretty quickly, mostly buses, which are very well organised but the crowds queuing and the traffic congestion especially around the station makes city travel slow and strap-hanging. Several times we visited the central shopping area around Gion and Kawaramachi-Shijo. If you can tolerate the crush of people, this is a fascinating area with the giant, elegant department stores, the labyrinth of lanes with every kind of shop and food outlets and the great market (which we missed). On our first day in Kyoto, we asked Maria at our ryokan (more about that later) where we should go to find dinner. Without hesitation, she said Pondo-Cho and told us to get the 207 bus to Gion. The swarms of people strolling and shopping were to us almost overwhelming. The rows of lights along the streets, the brightly lit shop fronts and the melodious chimes for all the street crossings made it all seem surreal.

Pondo-cho is unique. A long narrow walking street, maybe a kilometre long with the houses on one side opening on to the river, it is full of special interest shops, exclusive geisha destinations, dining clubs and intimate restaurants. We strolled along for a while, peeping into the establishments, nodding at each other and shaking our heads. I said, maybe here, or maybe there and mostly Sally said I don’t think so. Eventually she said ‘what about here?’ As almost always, I say ‘OK’ and we ducked into a tiny place where there was a counter beside the little kitchen. There were 4 or 5 people at the counter and I spied two tiny eating rooms near the river balcony where each held four people sitting on the floor. We took our place at the counter next to a woman who kept on shouting to the chef, ‘longer, longer!’ I thought she meant she wanted her meat cooked more so I gestured to the charming old Japanese chef accordingly, who quickly got my more empathetic approach to her demand. It turned out the couple sittiing next to us were Marie and Trevor who ran a scrap metal business on the Gold Coast and clearly had more money than sense. Sally was more impressed with Marie’s many facelifts than I was with the voice. I was rather won over by Marie as she guessed I was about 57 and nearly fell off her chair when Sally ungallantly told her the truth. However we had the most wonderful culinary experience in that little place with a long series of tiny dishes of every kind served to us, but the delicate tempura of fish and vegetables were the stand out to me. We drank a superb French Chablis and left knocked out by the subtlety of the food and its welcoming atmosphere. Much to their surprise, we returned the next night and had a different but equally delightful experience. When I asked the chef what the name of his establishment was, he help up a battered old frying pan with a friendly smile.

Kyoto’s traditional sites and gardens, usually connected to the temples and shrines, of which there seem to be hundreds, are mostly spread around the outskirts of the city, amongst the hills and woods surrounding the city. While we visited several, we only scratched the surface, but still had some remarkable experiences.

One day we walked the northern Higashiyama district for perhaps five kilometres after being dropped by a bus and walking to Ginkaku-Ji, a beautiful temple once the retirement villa of the emperor in the Middle Ages. We were more interested in the gorgeous autumn gardens that stretched up a verdant hillside with walking tracks and pools shimmering in the flawless sunshine, just about the first day of real sun we have had. The garden next to the lovely little lake features amazing mounds of raked sand, raked symmetrically with elegant traditional patterns. After leaving Ginkaku, we walked the Philosopher’s Path, literally a pathway along a little stream, under the shadow of the mountainside with little trees with autumn leaves along the way. Through a huge pine grove we came to a shrine called Honen-in, deep in the woods, very solemn. There was a room devoted to an art exhibition by an Japanese artist that seemed to me to epitomise the idea of deep Zen-like reflection. The paintings were of sombre natural settings: water, woods, branches of trees, all in dark greys, browns, blacks and suggestions of pastels, greens, blues and lilacs. Each one was overlaid with tiny bits of spatter, creating the effect of a sort of gauze between the viewer and the painting, making it seem even more remote and mysterious. I love them and wanted to take one home.

At the end of the Philosopher’s path, we found another extravagantly beautiful garden and temple called Eikan-do, and spent an hour admiring the colours, crossing the little bridges across the lagoons and watching two or three couples in traditional gear. Even with lots of people around, these secluded and colourful places exude peacefulness and tranquillity and you find yourself just standing and gazing.

It wasn’t all delightful like this. The hordes of people often got us down, despite their good humour. One day we travelled on a bus quite a long way to visit the Kyoto Crafts Museum as we’d met a Danish glass blower at the Frying Pan restaurant and she was exhibiting in another Danish Japanese exhibition at the Crafts Museum. It was all a bit boring and she had only two pieces in it so we decided to cut our losses and move on to the Kiyomuzu-dera Temple, one of Kyoto’s most famous. More crowded buses and then an endless trudge up a long steep hill lined with hundreds of garish stalls. There were so many people we were reduced to a crawl, made worse by lines of cars and taxi trying to make their way down hill. After an hour of this the temple and its surrounds were so packed, that we turned around and trudged back, tempers frayed and (my) feet and knees swollen and sore.

Sally was not happy with our accommodation in Kyoto, and I have to admit, nor was I, though it was I who organised it. I planned that in one city we should stay in a Ryokan, a traditional Japanese inn where you sleep in a futon on the floor and are given traditional hospitality including a multi court meal served in Japanese style. Ryokans are actually quite expensive because of the elaborate hospitality. Our ryokan in Kyoto turned out to be a ‘pretend’ Ryokan with the disadvantages of sleeping on a mattress on the floor, no tables or chairs, but also no special meals or service, indeed no food or drink at all.The only pluses were that it was clean and efficient and the girls at the desk were polite and charming. Spending six days groping around the floor was not a success.

Our day on the western edge of the city in the Arashiyama district was altogether a more pleasant experience. We wanted to walk through the famous bamboo forest and we did (with thousands of others). It was an eerie experience as the day became windy and blew the giant bamboo clumps all over the place, making a wild swishing, sighing sound. At the end of the bamboo forest we came across Omochi Sanso, a private retreat and garden created by a famous silent film samurai actor of the same name. 1000 yen to enter seemed a lot, but it was worth it just to escape the hordes and the garden turned out to be heavenly, in my opinion the most beautiful I saw on the whole trip to Japan. Immense trouble had been taken to juxtapose shrubs, rocks, trees, ponds, paths and vistas. Several tiny tea houses emerged from the paths and at one stage we reached a little ridge only to find we were overlooking a vast valley and stream way below with a huge mountainside facing us with a little temple in bright colours the only chink in the great slopes of pine trees.

In visits to foreign cultures in tourist mode, not knowing any or many individual people, it’s not surprising our most intimate experiences are often through the food. In Japan this is especially so, with such care being taken with its presentation and the frequency of small establishments with the kitchen in full view beside you. One night in Kyoto, we entered an open contemporary place, looking so attractive, only to find that it served only eel. Sally firmly decided salad was the only option for her, but I had a piece of grilled eel almost as long as your arm. Despite eel being a much relished delicacy inJapan, this was a mistake. The oily flavours and smell persisted in my consciousness until the next day.

But like our two visits to the Frying Pan, the food is usually a very satisfying cultural experience. One night wandering through the back lanes of central Kyoto we looked in at a little place where the young chef was at his counter and stayed. All he had was a small mesh cook top and a little blow torch, some sashimi, little cuts of meat and small piles of simple and exotic vegetables. Out of these meagre resources, plus an assistant to wash plates and serve, he fed 16 diners, eight at his counter plus four little tables. We had about six little courses, all carefully placed in front of us by him with the utmost charm.

On our last day in Kyoto, we again retreated to the fiesta on the edge of the city and climbed up to the amazing Fushimi Imari-taisha. It is a Shinto shrine consisting of thousands of vermilion torii, wooden squared gates or arches that you process through, the nearer ones quite massive but get smaller as you climb up into the forest. The path through the arches continues upwards through the forest and finally emerges on to the top of the highest hill where you look down on the whole of the city. Though Sally went to the top, after two weeks of walking up and down endless steep stairs, my knees gave way and I gave up half way up. It is a strange and mesmerising experience that got better the higher you go as the crowd thins as you go upwards.